indie soapbox

thanks for everyone who came to the indie soapbox in glasgow this month, where i got to give a small talk alongside simon meek. i've copied the intermittently-referred-to text below.

Hello, my name is Stephen and I've been in the knock-down drag-out big-money biz of making my own computer games as a hobby for the last 17 years, for reasons I can no longer recall.

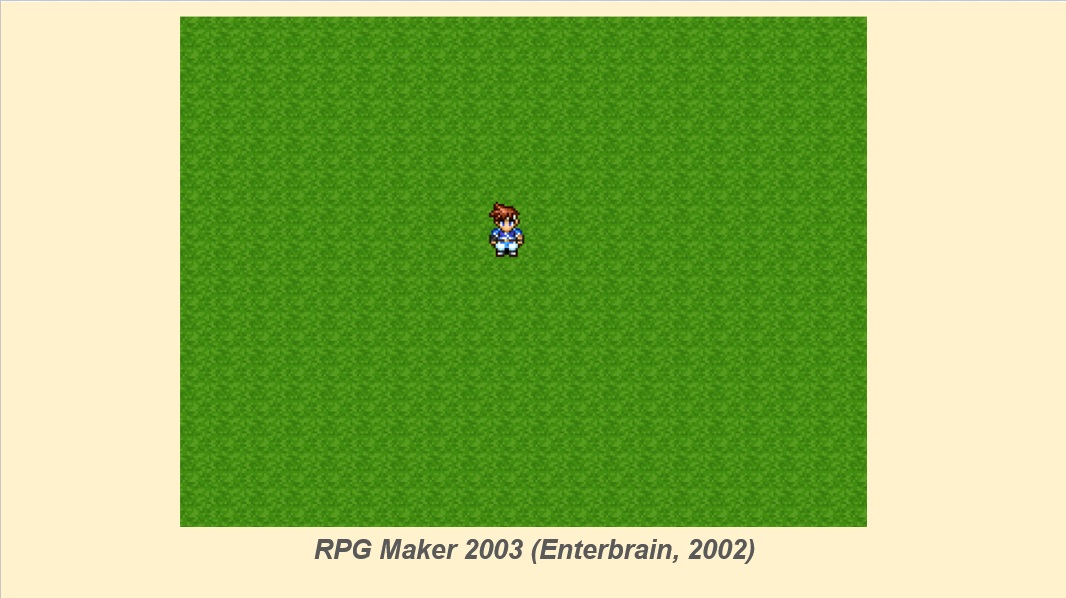

When I think about what drew me to the hobby, it was basically that I liked the feeling of moving a little guy around. I'd downloaded one of the free, pirated versions of RPG Maker as a teenager and when you fired up the program this was the first thing you'd see - a large and empty grass plain that you could wander around as the default player character. The game itself would have no content yet, no reason to move from one side of the screen to another. But for some reason I still found it compelling enough to keep on opening up and moving around in.

I think RPG Maker particularly is set up with an expectation that the game is more or less an excuse for content - that you'll put up with a certain clunkiness or limitation of the default verbs as long as you can add in your own little guys and start writing their stories. But my experience was that the content ended up being an excuse to keep exploring that clunkiness - that when I started adding battles and towns and dungeons and narrative elements, it was to have an excuse to continue coming back to whatever tiny, stupid thing I found compelling about just moving a guy around a field.

If I ended up trying to make a "real game" it's not so much that I wanted to as that I hoped that the ritual of game development would end up getting me closer to whatever it was I found interesting about RPG Maker itself, or about the computer itself, which was more or less the excitement of pushing a button and seeing something happen. Kind of in the same vein as the very first interactions I'd have with a computer - things like changing a screensaver, or the desktop background, or writing something in WordArt.

I think things like that can be hard to talk about with the language of orthodox game design, where the emphasis is more on things like challenge, or complexity, or conversation with the designer - the sense of an ongoing push and pull. The assumption here is of intentionality; that of trying to do something, and having this intent frustrated in some way. But what attracted me instead were trivial gestures - where you didn't even want something particularly, and found yourself doing it anyway without issue. To move from one side of another of an empty room, to change a screensaver from one preset to another. Things where neither the original intent or the end result are things you care about, but which nevertheless you find you're acting out.

One of my first memories of PC gaming was playing the flight game Crimson Skies - at the end of a level your character gets an ancient gold coin. And when the gold coin comes onscreen there's a button next to it that says "print". So I pressed the button to see what would happen, and the printer started whirring, and I got a print out of a golden coin I had no interest in, and could not spend.

To me part of the interest of computer games is the way they tend to act as snapshots for the decisions you didn't care about, for little drifts and scatters of attention that are lost as soon as they appear. You press a button without knowing why, you perform an activity without really wanting to, and you're confronted with this alienated, ghostly image of your own wandering mind in the form of a little sword guy squirming aimlessly across an empty field.

And to me that's both why I like videogames and why I don't like them. I don't like videogames because it can feel like the odd, empty hypnosis of watching your own thoughts play out in this way is almost too strong an effect to let anything else inside. I'll play a game, and I'll be moving the camera around and not looking at anything. I'll be hitting the button to talk to people and not reading any of the text. I'll play something for an hour and then feel like I've been doing nothing, that I've been doing less than nothing, not thinking, not even daydreaming. Because despite whatever accomplished thing the game insists I've been doing - killing people, acquiring gold - I've really spent that time just staring at my own reflection, at this glimpsed double of myself in the unnecessary actions that take place on the screen. And it can feel draining, as if to complete and fill out my doppelganger in the screen also means having to empty myself out - to dedicate myself totally to the task of pushing buttons in order to temporarily sustain this spectre, which vanishes like smoke as soon as I turn off the machine.

On the other hand, and despite this, I do keep coming back to videogames. And I think it's because I remember them so strongly - somehow the memory of videogames is always very potent to me. I'll remember a fragment of texture, or a functionless room, or the slippery feeling of grinding against some invisible collision box, and often these half-memories seem stronger to me, more charged and mysterious, than the experience of playing the game itself. It's as though the very empty, mechanical nature of that back and forth with the screen was also what allowed the elements of that screen to pass directly into the night mind without a filter, a kind of automatic writing in reverse. Or else that all the dead, indistinguishable time we spend with videogames were enough to make the little bits of them that survive in our heads seem even stranger, as if they were fragments of another game that never existed, some vast and invisible computer game it was our task to rediscover.

Maybe that's why memory is such a strong recurring theme in alternative computer games. Now before I continue that thought, I should say there are a few reasons why alternative games would keep returning to this theme.

The first is that "the future of videogames" has always been ringfenced by capital. It's always been seen as existing just over the horizon of ever more powerful home computers, high definition graphics and audio rendering, motion capture and so on. So to make a game with no investment capital is already to exist outside the future of videogames. Hobbyist games are read as "retro" no matter how much they do or don't resemble any actual particular computer games of the past. So for games in this space memory is a theme that's thrust upon them whether they want it to be or not.

The second is that these games often do in a sense exist in the past, in that they're often made in cheap and easy to use game engines reverse-engineered from the industry requirements of yesteryear. RPG Maker 2000 is a perfect example - a nonprofessional tool for making games in the style of the big budget games of a decade earlier. Even engines like Unity and Godot tend to be built on assumptions around how a camera works, or how a physics body should move, that have been established through the previous decade plus of cutting-edge commercial 3D games.

So these game editors are themselves built to be "gamey". Firstly in the sense that they are themselves repositories of videogame conventions; secondly in that trying to reach a nonprofessional audience often means trying to make the tools fun and gamelike in themselves; thirdly in that their use in tiny nonprofessional settings, where generating a new build to play is not this complex process, frequently means falling into a rhythm of tweaking things, playing the game, tweaking more things, playing the game some more. I guess what I'm getting at is the feeling that these game editors can themselves be games; that when I make a game in Unity, I am also playing a videogame called "Unity" and the game that comes out is a kind of byproduct of that experience.

Now, I'm not saying that's the case for all games produced this way. And often what gets canonised as "good game design" is specifically advice meant to push back on this tendency and make sure the end result remains intelligible as a work in itself - advice like consider the player, do regular playtesting, come at the work from an outside perspective and so on. But for people who are outside the industry and hence outside that expectation of an audience, this kind of memory sediment can be a powerful effect to explore in itself.

A third reason is that all computers are memory machines. They have memory, they use the metaphors of memory, they absorb and incorporate the imagery of previous memory technology like notepads, desktops, folders and reminders. A memory palace is a classical technique for retaining information by spatialising it - by constructing in your head a kind of virtual museum in which faces and names are stored in particular objects and locations. A home computer in this sense is also a spatialised memory container. And for anyone making videogames on a personal computer, full of old photographs and notepad fragments and letters from friends and things tucked into drawers, it can be hard to maintain a clear line between the two. The videogame can act as an extension of or a consolidation of the implied memory palace that is the computer in the first place. And for games made by hobbyists, people who might be working without structured design documents or meeting notes or changelogs, the game build itself can more literally than most end up being the museum for its own development. A place where fragments are heaped and sorted through and the lines between used and unused content may not be clear.

This is actually one of the things that most stood out to me about the famous early indie game Cave Story - the blurred quality of the game's storytelling, a sense of elements returning and mutating across all these discarded builds you'd never get to see, and the way this gave the game itself a sense of off-kilter density that I think would have been lost without that hobbyist game feeling of haphazardly accretting prototypes.

So those are three reasons why alternative games would keep coming back to the theme of memory. But what I'm interested in is actually a fourth reason. And to get at that one I'd like to bring up a different term first, the idea of the "motivation of the device". This is a term from the Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky, and in memory what it means is something like - in the novel Don Quixote, we tend to assume that the meaning of the work is something of a parody of the courtly romance. And the technique by which it's parodied is by playing the register of high-minded chivalry against that of a more down-to-earth and deflating everyday setting. So the idea that you have the intent of a work of art and then you have the tools that achieve it.

But we could as easily flip it the other way around, and say that what Don Quixote is about IS the startling literary effect of switching registers, of playing two forms against each other to unsettle and mutate them both in surprising ways. And where the nominal moral, the parody of knightly romance and about the dangers of reading too many books, functions as a kind of excuse or pretext for playing with these new effects. Instead of the moral or theme of a work as its ultimate meaning you have moral or theme as a device which enables new kinds of formal play. And I think the benefit of this framing is that it assumes this play of forms is generative beyond the theme of the work, that it's a strength rather than a defect when putting these things together seems to raise new and startling effects beyond what we expected from the stated theme.

To state a work is about something is to bring in some collection of pre-established images and associations for the thing to work off of. But it also clues us into what kinds of effects we should be looking for from the work itself. For a game to be about memory is to raise certain expectations - that it may be very personal, fragmentary or dreamlike. But there's also a deeper perversity, in that we're used to considering a work of art in terms of intent, while memory is by its nature unintentional. What we remember is often not what we'd like to remember, and it's often unclear why we remember one thing and not another. The things that lodge in memory may be good or bad, distinct or indistinct. We use the term memorable to denote things which are distinct and surprising in experience, but often the images of memory are indistinct in experience - the things we don't know that we've seen until we remember them later. A stretch of road, a bedroom ceiling.

Trying to deliberately cultivate memories can be to encounter this perversity head on. When I was young my parents took me on a trip outside Dublin, and I'm sure they were hoping that I'd have lasting memories of all the beautiful Irish countryside we drove through and all the picturesque small towns that we stopped at. The only thing I remember from these trips was a cigarette vending machine at one of the hotels we stayed at.

Now, a cigarette vending machine is a videogame. In many way a cigarette vending machine is the ultimate videogame - it's an image of technology and desire, control and volition and pleasure and addiction and money. I remember hanging out around it, aimlessly pushing the buttons and wondering if it would make something happen. And it's tempting to think that I remembered this one image because that experience, of pushing buttons and wondering what would happen, would be something I'd then explore in other ways for the rest of my adult life.

I think it's more true to say that anything in memory becomes a symbol - that any object of the world becomes a symbol, once it's severed from experience and returned to us through memory. An object is a world and also the vision of a world. And if alternative videogames are about memory I believe it's not so much that they want to be memorable as that they want to see what memory will turn them into. A memory game is one that accepts incompleteness in the hopes of someday being completed in some way they can't expect or recognize.

And of course all videogames end up being changed in unexpected ways by memory, but to recognize this in advance can be to change your own notion of what it is you're trying to make. It can seem more economical to make a 30min game that someone remembers 30 seconds of than a 30 hour game that someone remembers the same 30 seconds of. Rather than unity we might find ourselves making work that's fragmented, in hopes this better equips it to survive the fragmentation to come.

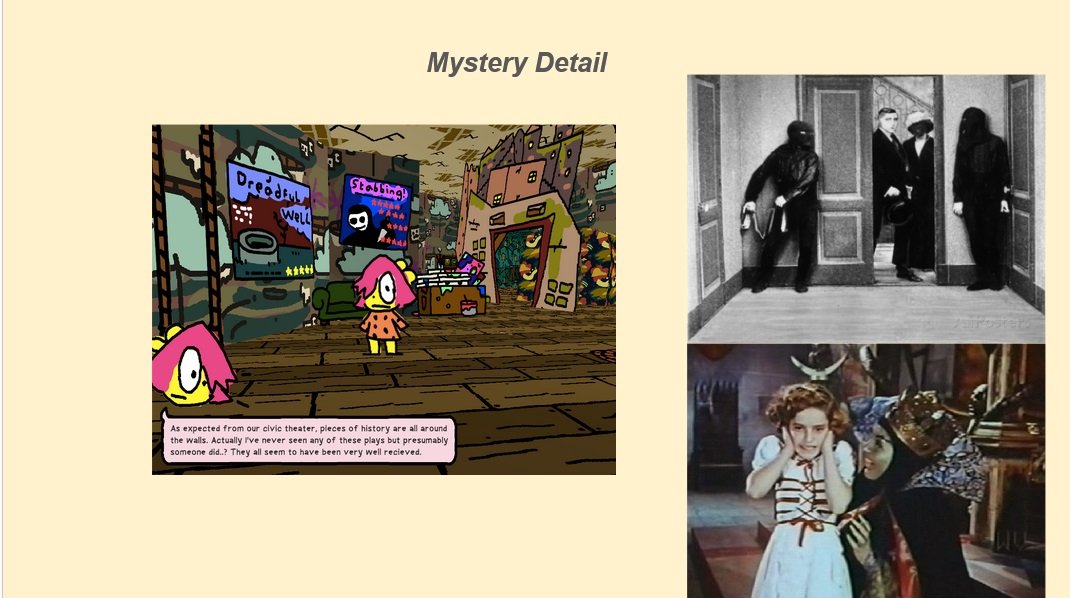

For the last four or five years I was working on little horror games in my spare time. They're often modelled on b-movies, and take inspiration from the scattershot nature of b-movies. The accidental effects, the way the tone can change from scene to scene, the hungriness of cheap art in the way it indiscriminately roams around looking to gobble up effects - the pattern on a piece of wallpaper or upon somebody's dress, the face of a particular character actor, stray lines of aspiring crude or poetic dialogue. A comics artist I liked a lot, Richard Sala, talked once in an interview about a time in his life he dedicated to watching b-movies - they'd always be on the TV at 2am so he'd set an alarm, get up at 2, watch the movie in the dark, and then climb back into bed and sleep. He said it felt like the perfect way to watch these things, as if they were dreams you were half remembering the next day.

And when I made horror games I liked to imagine them being played by someone who was half asleep, the hope that the games themselves somehow made sense or remained intriguing even if you weren't paying attention, if you were drifting in and out from scene to scene. That the narrative would make a kind of emotional sense, but that all the stray details, little lines of dialog or ideas or the question of how one thing related to another, might stay with us instead as half-remembered mysteries. Shapes we fill out with ourselves in a different kind of recognition to what plays out on the computer screen. I'm interested in games that destroy themselves on screen the better to be played in memory.

Of course, the flaw in my argument is obvious to anybody listening. If we can't anticipate what we will or won't remember then there's no reason to think a game structured as memory will really be any more memorable than a game structured after anything else. Whether it's experimental narrative or FIFA the memory will take what it will and discard the rest, and eventually return with something rich and strange.

And despite my talk about the empty feeling I get from playing videogames, I'm not really interested in suggesting anything that's better or more moral. What intrigues me about memory is in fact that it's so totally amoral. In a way it seems to me a model of what Keats meant by the term "negative capability" - "when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason"...

And something of this negative quality, this willingness to exist outside of positive reasons, is I think what I always found most beautiful and astonishing about videogames themselves, about cigarette machines and RPG Maker games and all the aimless and directionless mazes of perception as embodied in these things. So maybe the virtue of memory as a theme is that of setting yourself an impossible task, one whose success or failure can't be measured, one we can't QA test for - I don't think there are any videogame playtesting sessions where you ask someone to play a thing and then come back ten years later and tell you what they thought. That the undecideability of the task could be a form of fidelity with the undecideability of the format itself, a dream of living without knowing exactly what it is we represent.